7

Toward a Paradigm for Reading Hypertexts:

Making Nothing Happen in Hypermedia Fiction

"…poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper…" W. H. Auden, "In Memory of W. B. Yeates"

"Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again."Shakespeare, King Lear

Literature is a dying art. This statement is not a prophecy of doom but a paradox: literature is never more alive than when it is dying. Virtually every moment of literary history has struck some writer as the end of the road, the point at which serious, important, or valuable writing becomes impossible. The cultural coroners ordinarily focus on genre: the death of tragedy, the twilight of the epic, the demise of the novel, the collapse of parody. But the rise and fall of genres usually coincides with technological change. For instance, the novel came into its own only when advances in printing and the availability of cheap paper permitted the mass production of inexpensive books. Now the novel and other print genres seem threatened by the evolution of hypermedia, which Steven Levy recently branded "the end of literature" [Levy, 1990].

Literature never ends; it survives. Levy and other media critics base their doom theories on a zero-sum model of evolution in which any gain for new technologies depletes the old. Obsolescence means displacement. Yet the historical development of media patently contradicts this view. As Marshall McLuhan observed, "the content of any medium is always another medium." [McLuhan, M., 1964] More advanced technologies incorporate those that come before. Writing contains speech, print contains writing, film contains both these media, as when a voiceover accompanies a montage of headlines. Hypermedia, the latest of McLuhan's extensions of man, unites sound, graphics, print, and video.

Writing Survives, But In a Changed Environment

Once upon a time, when literary critics used the word "text" they meant a verbal artifact – a book or manuscript. More recently that term has come to stand for any network of symbols, verbal or otherwise: film as text, seminar as text, history as text [Barthes, 1979; Fish, 1980; White, 1973]. This latter, more expansive notion of "text" seems a better way to understand hypermedia productions and the role writing plays within them. The printed word is no longer the dominant medium, but only an element in a technological synthesis, one strand in a complex text.

We face the advent not of electronic books, but of eclectic multimedia compositions that assimilate and transcend the book. The future of literary expression is not a linear progress in which new technologies of expression usurp old ones. It is more likely to be a recursion, a widening gyre in which new forms merge and coevolve with their precursors.

The term “recursion” has several connotations. It implies the neat cyclicality of reflex and reiteration, as in the hierarchical nesting of functions in a computer program. Recursion in this sense is a rational process, analogous to the revolution of gears in an engine or the closing of circuits in a microprocessor. But there is also a second, irrational meaning of recursion. This is the sense invoked in Douglas Hofstadter's notion of tangled hierarchies, where an apparently orderly procedure yields paradoxical results [Hofstadter, 1979]. As in M.C. Escher's surrealist Waterfall, where tricks of perspective make a downgrade seem to lead upward, this irrational recursion invalidates our sense of hierarchy and shatters our interpretive framework.

Tangled hierarchies and "strange loops" may be our most powerful modes of expression at this late moment of the Twentieth century. As the cultural critic O.B. Hardison observes:

A horizon of invisibility cuts across the geography of modern culture. Those who have passed through it cannot put their experience into familiar words and images because the languages they have inherited are inadequate to the new worlds they inhabit. They therefore express themselves in metaphors, paradoxes, contradictions, and abstractions rather than languages that "mean" in the tradi tional way-in assertions that are apparently incoherent or collages using frag ments of the old to create enigmatic symbols of the new. [Hardison, 1990]

Hardison has in mind Dadaists, surrealists, and expressionists, the first artists to step over the modern event horizon. These figures represented an avant garde dedicated to subverting old orders of meaning. They accomplished this subversion by exposing the fonnal mechanisms of language, building poems out of abstract sounds, typographic manipulations, or random numerical sequences.

But that was a long time ago. At century's end, some critics argue, we have outgrown or exhausted such rebellious impulses. Our culture has passed from modern to postmodern, and there are those who say that avant garde art is impossible under postmodernism [Eagleton, 1985]. Many reasons are proposed for this situation, most having to do with the inability of artists to separate themselves from pervasive ideological and informational systems. Modernists could renounce traditional culture by embracing absurdity. Postmodern culture is always already meaningless. Any provisional meaning it can muster arrives predeconstructed, already defined as the sort of arbitrary, self-referential sign system that the modernists strove to create. It is impossible to be a Dadaist in a Dada universe.

Our universe is Dada with a difference, however, and the name of this difference is technology. Our capacity to build and manipulate complex informational systems has increased hugely in the second half of the century. From market analyses to programmed stock trading, we live in a world in which abstract models are increasingly based not upon any observed fact but upon other abstract models the world of the hyperreal. Hardison has argued that our sense of reality is disappearing through the skylight as we replace nature with convincing images of reality. The world we have built may be absurd – not grounded in any value or sense of destiny – but it is eminently systematic.

Since technology is strongly implicated in the disappearance of the real, what possibilities are there for technological fiction? Is it possible to make meaningful or critical statements about complex, self-referential systems from within a hypermedia text, which is just such a system? Is this really the end for literature?

Even as theorists of the postmodern toll yet another death knell for yet another artform, undismayed artists have begun to explore the expressive potential of hypermedia, turning systems recursively back on themselves to probe the seams and fissures of the hyperreal. In the section that follows, we examine an exemplary hypermedia fiction.

An Example of Hypermedia Fiction

on mouseUp

Global thennoNuclearWar

put the script of me into tightOrbit

put tightOrbit into eventHorizon

put empty into first line of eventHorizon

put empty into last line of eventHorizon

put empty into last line of eventHorizon

put eventHorizon after line thennoNuclearWar of tightOrbit

set the script of me to tightOrbit

put thermoNuclearWar + 10 into thermoNuclearWar

click at the clickLoc

end mouseUp

The HyperTalk script shown above is a very small part of Uncle Buddy's Phantom Funhouse (© John G. McDaid) a work-in-progress by hypermedia artist John McDaid.

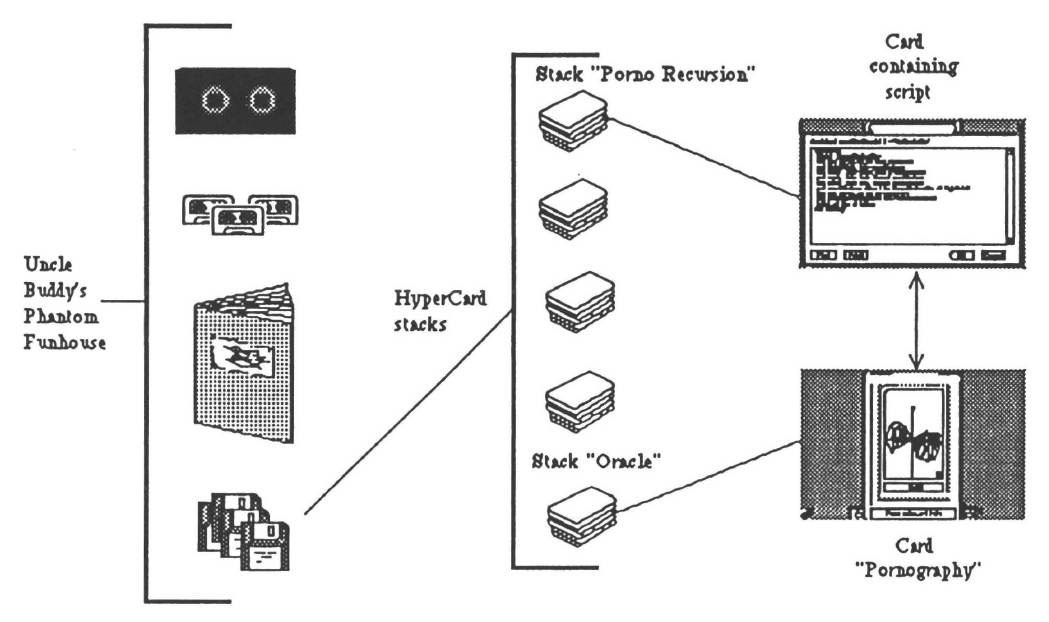

The Funhouse is a complex fabric of texts within texts (See Figure 7.1), consisting of video and audio tapes, photographs and drawings, letters, offprints, galley proofs, and a set of Macintosh disks, all purporting to be the effects of a disappeared writer, one Arthur "Buddy" Newkirk.

Uncle Buddy's disks hold a series of electronic documents which themselves contain a variety of printed words, images, and digitized sounds. Since these documents are hypertexts (HyperCard stacks), many of their elements are cross-linked both within and among documents.

Though there are abundant connections between Uncle Buddy's various fragments, the reader is given no clear instructions for their assembly. The details revealed by the text do not integrate into any single, exhaustive narrative. The exhibits in the Funhouse are capable of multiple arrangement and signification, making Arthur Newkirk potentially many things to many readers. Implications abound, but there is no deductive problem to solve, no imperative to recover in any definitive sense the lost art.

Yet even though the hypertextual labyrinth conceals no kernel of meaning, certain of its elements are especially significant, and the script shown above is one of them.

The script is technically untitled, but for convenience we will give it the name of the stack to which it belongs, Porno recursion. This stack is one of several apparently created by Uncle Buddy and copied to the backup disks included in his effects. When the contents of these disks are transferred to the reader's Macintosh, they provide access to Uncle Buddy's virtual reality, a densely interlinked network of notes, sketches, drafts, and correspondence.

The primary interface between the reader and this mass of information is a simulation of Newkirk's house in Pirate Cove, Rhode Island. Each room in the house is represented by a series of digitized photographs which the reader can tour by maneuvering a pointer on the Macintosh screen.

During this exploration the reader can manipulate objects in the house, opening doors, windows, drawers, and cabinets. The house provides a symbolic index or organizing metaphor for the entire set of HyperCard stacks, acting as the electronic equivalent of a memory palace. Objects or locales in the house are hypertextually linked to various electronic elements of the fiction. For example, opening the mailbox in front of the house, calls up a stack containing a log of Uncle Buddy's correspondence on a computer network. By manipulating the house and its furnishings, the reader can access several documents and objects, including notes for a screenplay, an annotated sketchbook, an electronic literary magazine, (Source Code, the HyperMagazine of Hacker Poets), and a modified Tarot deck called Oracle.

It is through the Oracle deck that the "Porno recursion" script comes to light; but as with the conventional Tarot, the path to enlightenment requires patience and ingenuity. The link between Oracle and the "Porno recursion" script is neither simple nor immediately apparent. To discover it, the reader needs to recognize that the Oracle stack initiates a dialogue between new media and old.

The elements or nodes in a HyperCard stack are referred to as "cards, " following the file card analogy developed in Xerox PARC's NoteCards program. In Oracle, McDaid/Newkirk plays on this analog, patterning his electronic cards after actual, cardboard artifacts. In fact, the images on each virtual card were optically transferred from a hand-drawn deck. Like the original arcana, these hypertextual cards can be laid out or accessed in sequence, and thus interpreted for cryptic significance.

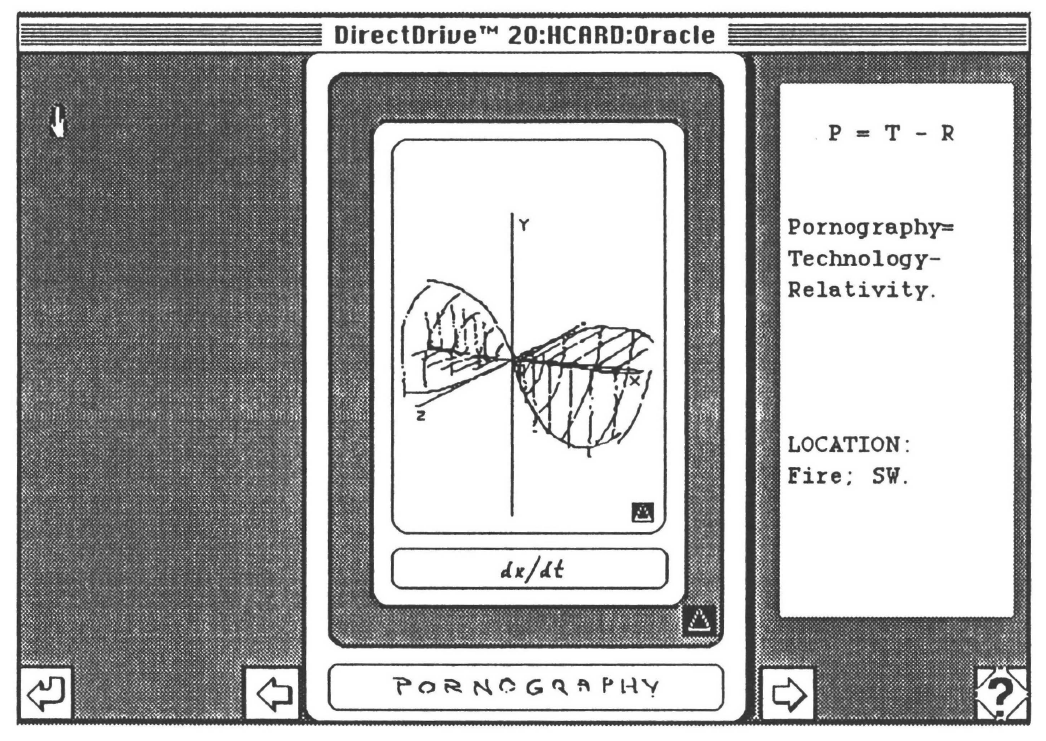

But there is a crucial difference between the electronic Oracle and the traditional Tarot. Material Tarot cards are formally stable and discrete. The Oracle cards, by contrast, may not display all of their graphic and verbal content on first presentation. Since the stack Oracle is a hypertext, any visible writing or image may act as a pointer to additional content. This hidden content is displayed when the reader finds a hot area or button with the pointing device. The link that takes us to the "Porno recursion" script is triggered by a button installed on an Oracle card called "Pornography" (See Figure 7.2).

The figure on this card shows the graph of an electromagnetic waveform of the type that might be used in radio or television broadcasting. There is also a gloss to the image, "P = T – R: Pornography equals technology minus relativity. " Presumably this emblem and its gloss have some connection to the "Porno recursion" script; but the script is not directly attached to the card or its image. Technically speaking, the script resides on another card altogether, one that does not even belong to the stack "Oracle. " (The reason for this inconsistency will be clear below.)

Since the script is not visible from the Pornography card, no casual browser through the Oracle will discover it. The script is revealed only to readers who learn to consult the cards for hypertextual links as well as textual symbolism, keeping in mind the fact that everything in Uncle Buddy's universe is potentially connected to everything else.

HyperCard provides a keyboard command that shows the location of any link buttons on a given card. Used on the card Pornography, this command reveals several buttons, one of which (the smaller black triangle immediately below and to the right of the line drawing in Figure 7.2) opens the pathway to the Porno recursion script.

Pressing this button brings up a dialog box containing the warning, "Too much recursion" (See Figure 7.3).

This standard HyperTalk error message occurs when the order of operations in a script becomes confused or tangled, for instance when a routine enters a loop in which it calls or activates itself interminably. Presumably something has gone wrong. The HyperTalk script activated by the button cannot be executed because of a serious logical flaw. The Funhouse, it would seem, is not entirely up to code.

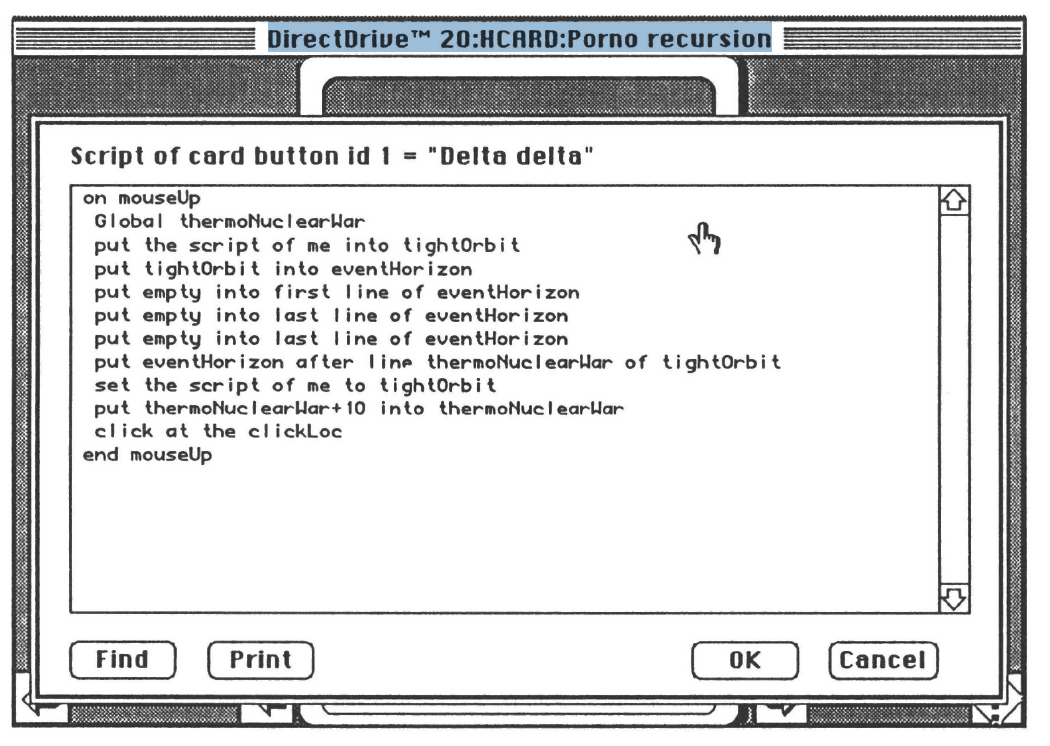

But this apparent breakdown is only the beginning of what will prove to be an extremely complex interaction. The error message dialog box in HyperCard contains a button allowing the reader to edit the script that has just failed. If the reader takes this option after the "Too much recursion" message comes up, the code that appears is the "Porno recursion" script, which has ostensibly crashed after being activated by card button Delta delta on card Pornography (See Figure 7.4).

The interactive pathway leading to this discovery is notably twisted. We seem to reach the script only by accident, when an unforeseen flaw in the functioning of the Funhouse exposes the infrastructure of the text. In fact this is not the case – the error message is part of an elaborate deception – but the nature of this deception cannot be explained until we have looked more closely at its immediate implications. For the moment, it suffices to note that the apparently unplanned appearance of the "Porno recursion" script is essential to its cognitive effect. Accidental or not, the script's eruption opens a rift in the primary illusion of the text, shattering the seamless functionality of Uncle Buddy's docuverse. Like Dorothy on her way out of Oz, we cannot overlook what we see behind the curtain.

The revelation of the "Porno recursion" script apparently breaks the fictional frame, confronting us with a mechanism (and a language) that would otherwise have remained concealed. We undergo what Hofstadter would call a jump out of the system [Hofstadter, 1979], a sudden shift in our mode of interpretation.

In this case this jump is also a recursion in media. Until the moment of apparent breakdown, we have interacted with the Funhouse as a multimedia hypertext, a complex, interconnected work informed by elaborate graphic and other metaphors. But the "Porno recursion" returns us to the ostensibly coherent, linear mode of print. After all, a HyperTalk script is fundamentally nothing more than a sequence of typed characters. The error that arrests Uncle Buddy's Oracle would seem to throw us back to a primitive level of function. It seems to demonstrate that all the brave machinery of the Funhouse depends on the printed word.

According to this interpretation, the recursion to print represents a change of levels within a stable hierarchy: higher-level functions have broken down, revealing what lies beneath. But this is only part of the story behind the "Porno recursion. " To see the emergence of the script as a simple hierarchical shift is to assume that "Porno recursion" is a conventional piece of HyperTalk code – but it is plainly more than that. While HyperTalk permits the writer of a script to call variables almost anything, the choice of thermoNuclearWar as the name of the counter in the second line indicates that there may be more at issue here than simple functionality. The arresting line: "Global thermoNuclearWar" suggests that "Porno recursion" returns us not just to print, but to print as a medium of literary expression. The script is really a poem in disguise.

This is not really such a strange suggestion. High-level computer languages share many formal qualities of verse: verbal economy, line breaks and enjambments, organization into functional units (think of subroutines as stanzas). The "hacker poet" is not such a rare beast; it is not unusual for variable names or comments in a program to constitute a quasiliterary subtext. But ordinarily these poetic overtones remain latent or superficial, while in the "Porno recursion, " they take on crucial significance. If we would understand what the script is really about, we must read it as a poem.

Script As Poem

The "Porno recursion" poem is a satire on systematic language. It launches a probe into the dark undertones of HyperTalk's utilitarian vocabulary. The Ianguage of programming is ostensibly unambiguous and purely functional. Declaration statements pass information about the type and name of variables; assignment commands associate information with those variables; selectors refer to specific items in a block of data. Ostensibly, these expressions mean nothing more than what they do.

The script-as-poem overturns that assumption by loading the plain language of programming with allusion. In literary terms, it employs a device called infection, a combination of guilt-by-association and conditioned response. The object of this device is to "contaminate" a supposedly neutral expression by associating it with language that is not so neutral, so that when the target expression reappears in an innocent context, it will carry an "infected" connotation. So the declaration syntax global [variableName] yields a "declaration" of Global thermoNuclearWar. Likewise, the assignment command put suggests the tactics of pre-emptive strike (put the script of me into tightOrbit) and the selector last is used to invoke apocalyptic singularity (last line of eventHorizon). The twelve-line programming script is thus transformed into a vision of the end of the world.

Thus "infected," the narrow language of programming opens onto a distinctly sinister perspective. It is appropriate that this parodic distortion comes out of the Oracle card Pornography with its anti-technological gloss ("Pornography equals technology minus relativity"). The oracle of the card seems to warn that a determinist, unrelativistic application of science leads only to debased conceptions conceptions which must include the apparently innocuous technology of the Macintosh itself, whose symbol of system failure is after all an iron bomb. Through poetic juxtaposition, Porno recursion reveals the connection between the "global" control that allows us to construct systems like hypermedia texts and the will-to power that motivates us to produce nuclear arsenals. As Susan Sontag put it, "cogito ergo boom."

But the process of conversion from script into poem is itself highly significant. To read a brief HyperTalk script as verse is to tangle the hierarchy of hypermedia. Allusive, literary meaning is supposed to be found only at the higher levels of the text, at the level of the virtual reality. Programming scripts belong to a lower, merely functional reality. This print infrastructure is not ordinarily so loaded with meaning. "Porno recursion" demonstrates that this hierarchy is inherently unstable in hypermedia fiction. The constraints of functionality cannot suppress the evocative potential of printed language, which may erupt whenever there is "error," exposing the linear, causal structures that underlie the supposedly "nonsequential" interactive text.

Funhouse As An Example Of The Interactive Medium

But the nature of this "error" in the Funhouse needs further explanation. In fact, it is no error at all, but a carefully arranged object lesson about the nature of the interactive medium. We have so far considered the script as a jump out of the system in which programming asserts itself as poetry. To fully appreciate the significance of "Porno recursion, " however, we need to reverse interpretive course again, moving from the allusiveness of literature back toward the functionality of

computer code. But to do this we flrst have to untangle the multiple deceptions in which the script is embroiled.

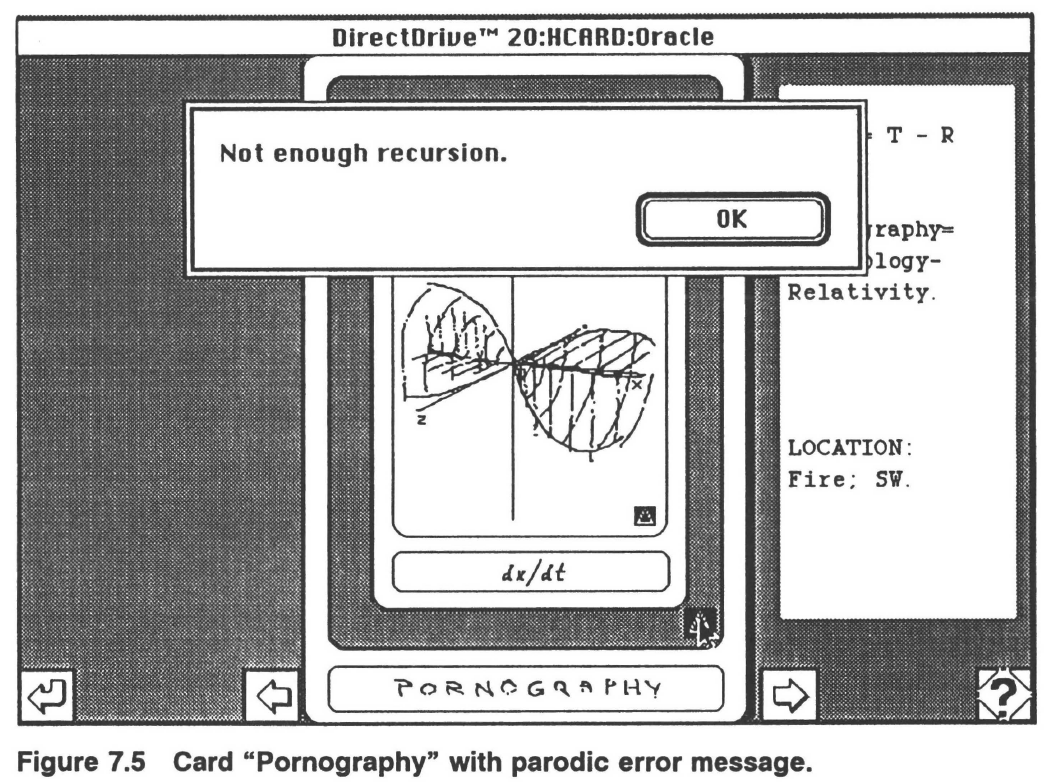

"Porno recursion" appears to be a flawed HyperTalk script activated by card button Delta delta. In fact this is not the case, and an alert or skeptical reader has several ways to detect this. The Pornography card contains a number of buttons besides Delta delta. Pressing one of these buttons, the larger black triangle below and to the right of Delta delta brings up a dialog box reading, "Not enough recursion. " (See Figure 7.5.)

This patently nonstandard message clearly suggests we are in the realm of parody.

Even more revealing is the title bar of the screen containing the "Porno recursion" script (see top of Figure 7.4). The location string here indicates that we are no longer viewing a card in the Oracle stack. If the flawed script had been activated from a card in that stack, the title bar would contain the name Oracle, not "Porno recursion." Clicking on the Delta delta button activates a link between stacks-a link whose operation is very hard to notice, since the one card in the stack Porno recursion exactly duplicates the background of the Oracle card from which we departed.

The jump to a second stack confirms the suspicion that we have left the ordinary programming conventions of HyperCard. Indeed nothing about "Porno recursion" and its apparent failure is what it seems. The script is not activated by the Delta delta button; in fact it is never executed at all. The warning of "Too much recursion" is a false alarm, produced in the same way as the bogus "Not enough recursion" message, by use of a HyperTalk command that generates dialog boxes. The "editing window" in which the script appears is actually an ordinary display field offering no ability to edit scripts. Since the script does not appear in a real editing field, it is not executable code.

But the enigma deepens. While the "Porno recursion" script is not presently executable, it does have all the formal properties of a viable program. The ambiguous nature of the script cuts both ways; if it can be read as a poem masquerading as unit of programming code, we might also entertain the notion that it is a valid HyperTalk script disguised as a script disguised as a poem. This may seem an excessively paranoid approach, but it has been said that paranoia is "the realization that everything is connected" [Pynchon, 1973], and in the multi-linked environment of hypermedia this seems a useful way of seeing.

A sensitive (or paranoid) reader might begin to wonder how the "Porno recursion" script would operate if it were removed from its fraudulent context and attached to an actual HyperCard button. Indeed, any reader who has ventured this deep into the complexities of the script and its appearance should have little trouble creating a new button and copying the script into its editing window. These are relatively simple operations in HyperCard, and since the Funhouse allows its reader to add to or modify its structures, they are entirely possible. All that remains then is to press the button.

Here is what happens when the "Porno recursion" script is set up and executed:

thermoNuclearWar. The next instruction commits the first of two recursions: the script copies the text of itself into a variable called tightOrbit, which it then duplicates in a second variable called eventHorizon. The version of the script placed in eventHorizon undergoes some editing and is concatenated with tightOrbit at a point determined by the counter. The value of the counter is increased by 10, so that the material contained in eventHorizon is added to a progressively longer text in tightOrbit.

The penultimate line of the script ("click at the clickLoc") represents a second, more dangerous form of recursion. This instruction tells "Porno recursion" to send itself the same signal (a "mouse click") that activated it in the first place. In other words, Porno recursion reruns itself from the beginning, creating a theoretically infinite loop.

But since the script builds progressively larger versions of itself, its self-modifying recursion quickly produces a text so large that it cannot be processed. Running on a Macintosh Plus, "Porno recursion" exhausts available RAM in about eight seconds. The result is not an error message but quite literally a jump out of the system (or the system software). Having run out of memory, HyperCard is forced, as Apple documentation puts it, to "quit unexpectedly." All processing in the Macintosh stops. There should be no permanent loss of data, but no further instructions can be executed until the computer is manually restarted, wiping out the present contents of RAM. Running the "Porno recursion" script brings the reader's tour of the Funhouse to a dead halt-which is doubtless the reason why the script is initially presented in nonexecutable form.

Though this elaborate subterfuge does amount on one level to a practical joke, it is also much more. To begin with, the script's operation as program connects to and reinforces its meaning as satiric poem. Executed on the Macintosh, "Porno recursion" becomes a parable-by-simulation about apocalyptic thinking. Consider the action the script performs: a recursive rewriting of itself. A script about nuclear war writes a bigger script about nuclear war that writes an even bigger script about nuclear war, and so on till the crash comes. Nuclear discourse pornographically feeds on itself, replicating unchecked, until all available memory (which might stand for discursive energy, or even capital) has been expended, at which point everything stops dead.

lnterpreting Hypermedia

But though this script seems directed at the perils of systematic thinking in general, it has a particular (recursive) relevance for the kind of system called hypermedia. "Porno recursion" shatters its own electronic universe in several ways, both interpretively and practically. The script exposes itself and invites the reader to fool around – with consequences that can get reader and text quite literally arrested. In this regard the epigraph McDaid applies to the Funhouse has particular resonance: it is John Barth's question, "For whom is the funhouse fun?" Clearly one function of the "Porno recursion" is to spoil our fun, to deconstruct the fiction's value as entertainment, and by extension, to call into question the value of any "entertainment" that relies on a self-enclosed interactive system.

But even though the Funhouse refuses to entertain, it does enlighten. The "Porno recursion" teaches a series of lessons about interpreting a hypermedia text. On one level, it demonstrates the difference between the kind of "interpreting" that microchips do and the allusive free play that distinguishes human language from machine code. Uncle Buddy's diabolical script turns the computer into a suicidal automaton, forcing it to engage in an activity that will ultimately render further activity impossible. But the code as presented to the reader exists not as execut able statements but as allusive, poetic language. The human reader may thus do what the mechanical reader cannot-process the instructions but refuse to execute them, consider the sequence of actions prescribed in the program and elect not to put them into play.

This exercise could have considerable value as an object lesson. In a world where the "global variables" of power and knowledge tend to orient themselves toward singular, hegemonic world orders, it becomes increasingly difficult to jump outside "the system." And as Thomas Pynchon reminds us: "Living inside the System is like riding across the country in a bus driven by a maniac bent on suicide." [Pynchon, 1973]

The "Porno recursion" might point the way to a response. By learning about our place on the bus (and by learning what messages are passing through the bus), we may be able to unseat the madman at the wheel. Failing that, we might at least be able to slow down, reroute, or disable the bus-possibilities for which the "Porno recursion" represents a significant raising of consciousness.

Suppose we surrender to the seduction of Uncle Buddy's "pornographic" script. What wisdom do we gain by installing and running a program that is designed to crash our machine? One way to answer this question is to suggest that there is cognitive value in such an exercise. When Auden asserted that "poetry makes nothing happen" he doubtless did not have in mind Uncle Buddy's idea of textual paralysis. But then again, Auden lived in a world without microcomputers, hypermedia systems, and virtual realities. The act of making nothing happen in McDaid's recursion may have powerful symbolic value, both as a demonstration of the danger of nuclear discourse and as a reflexive critique of hypermedia and other semi-autonomous systems. The sabotaged "Porno recursion" reverses Hardison's process of "disappearance," confronting us not with a seamless techno logical theatre but with a little world cunningly disarrayed. The jump into the infrastructure in "Porno recursion" gives hypermedia fiction a critical agenda.

The script and its complexities show us what is at stake in interpreting hypermedia texts. According to the literary theorist Martin Price, the "fictional contract" holds that "to read a novel is to discover the order latent in its materials rather than simply to impose one by a set of rules." [Price, 1983] Hypermedia fiction calls this proposition in question by collapsing its primary distinction. McDaid's script demonstrates that the order "latent" in a narrative is never anything but a set of rules in the first place. But to assume that a reader is free to "impose" new rules even in a hypertext is dangerously naive. The "Porno recursion" reminds us of this by laying bare its artifices, showing us the manipulative mechanisms that underlie the apparent "freedom" of interactive reception.

This experience can be most enlightening. Hypertext is not necessarily a liberation. We may change the text only if we can change the rules; but first we must be able to read the rules, which exist in an underlying layer reachable only by persistent inquiry. If we would come to terms (or to grips) with this level of the text, we must be prepared to execute our own readerly "recursion," moving from the free play of poetic discourse back to the purposiveness of scripting languages. But in making this return we must be willing to negotiate a new fictional contract, one in which we acknowledge that any literary undertaking in hypermedia is itself implicated in a discourse of power and control. We should be willing to interrupt this discourse; but we can do so only if we are willing to decompile as well as deconstruct.

About the Author

Stuart Moulthrop

Stuart Moulthrop is Assistant Professor of Literature, Communication and Culture at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He has published several papers on hypertext and interactive technologies and recently completed a book on contemporary American fiction. He has given presentations at numerous trade shows and conferences, including HyperExpo, Hypertext '89, and InterTainment.

His works in progress include Creatures and Creators, a hypermedia cross-edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and James Whale's 1931 film, and Chaos, a hypermedia fiction. With Michael Joyce, Nancy Kaplan, and John McDaid, he is a founding member of the TINAC fiction collective.

Mr. Moulthrop may be contacted in c/o Department of Literature, Communication and Culture, Georgia of Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332.

References

Barthes, R. (1979). J. Harari (Ed.), Textual Strategies: Readings in Poststructuralist Criticism, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 73-81.

Eagleton, T. (1985). "Capitalism, Modernism and Postmodernism, " New Left Review 152, 60-73.

Fish, S. (1980). Is There a Text in This Class: The Authority of Interpretive Communities, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Hardison, O. B. (1990). Disappearing Through the Skylight: Culture and Technology in the Twentieth Century, Viking Press, New York, NY.

Hofstadter, D. (1979). Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Basic Books, New York, NY.

Levy, S. (1990). "The End Of Literature: Multimedia Is Television's Insidious Offspring," Macworld, June, pp. 61+.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Price, M. (1983). Forms of Life: Character and Moral Imagination in the Novel, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Pynchon, T. (1973). Gravity's Rainbow, Viking Press, New York, NY.

White, H. (1973). Metahistory, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. MD.