6

Composing Hypertext: A Discussion for Writing Teachers

Hypertext is a new medium, in my view, because it is intimately tied to the computer; the true hypertext or hyperdocument exists and can exist only on-line, and has no meaningful existence in print. If I am right in making this claim, then it follows that we will need a new set of theoretical principles to describe how hypertext works as a medium. I don't propose to define a new rhetoric in these few pages, though I have made a preliminary attempt elsewhere to address some of the conceptual issues hypertext raises [Slatin, 1990]. Instead, I'll try to explore some of the practical problems hypertext might pose for teachers of writing.

Defining Hypertext

Theodor Holm Nelson, who coined the term hypertext in the mid-1960s, says that hypertext is any piece of "nonsequential writing" [Nelson, 1987, 1/14]. Newspapers and magazines, whose layout require us to read non-sequentially, are examples of what Nelson means; so are encyclopedias and other reference books, heavily cross-referenced and generally not meant to be read from beginning to end; and I have written elsewhere that hypertext resembles poetry in its intertextuality [Slatin, 1988]. But I cannot agree that encyclopedias and poems are already hypertexts; they can more properly be described as forerunners. Although these examples have what some might consider the virtue of making hypertext seem familiar and therefore nonthreatening, they are also quite misleading, as I shall explain below.

Nelson says that the hypertext concept is not intrinsically dependent upon the computer. I believe, however, that true hypertext can only exist on-line. So I want to modify Nelson's definition, to read as follows:

A hypertext (or hyperdocument) is an assemblage of texts, images, and sounds-nodes-connected by electronic links so as to form a system whose existence is contingent upon the computer.

The user/reader moves from node to node either by following established links or by creating new ones. The conventional text is the result of many individual choices made by the author from among the available alternatives. By contrast, the hypertext consists of many possible or virtual texts, which may be the work of different people. The reader actualizes one or more of these virtual texts in choos?ing which links to follow and which to ignore.

The potential significance of this difference is most clearly evident when we consider the vexing problem of hypertext's relation to print.

The Goal of Hypertext

Both word processing and desktop publishing have had an enormous impact on the practice of writing, as I have already said, and, like hypertext, both are inconceivable without the computer. What separates them from hypertext, however, is that both word processing and desktop publishing have as their goal the production of printed documents.

That is not the goal of hypertext. In my view, there is no such thing as hard copy of an entire hyperdocument. A printout of all the nodes would probably be meaningless, since it would lack even the provisional, temporary structure created by the reader's choices as she moved through the hypertext system. By the same token, a printout consisting only of the nodes accessed during a given session inside a hypertext actualizes a particular pathway through the material, a particular sequence, a particular set of choices. But it isn't the hypertext, any more than a given critical reading of a poem is the poem. What hypertext really requires is enough storage space to keep everything available on line.

Composing Hypertext

Leaving aside the financial implications of what I have just proposed, readers will naturally be asking a number of other, equally practical questions at this point. For instance, if we are seriously proposing to allow or require students to compose their essays in hypertext form, and if we accept the contention that hypertext can't be printed out, then we have to ask how students are to hand in their work. We also have to wonder what these hypertext essays will look like and how we are supposed to evaluate them.

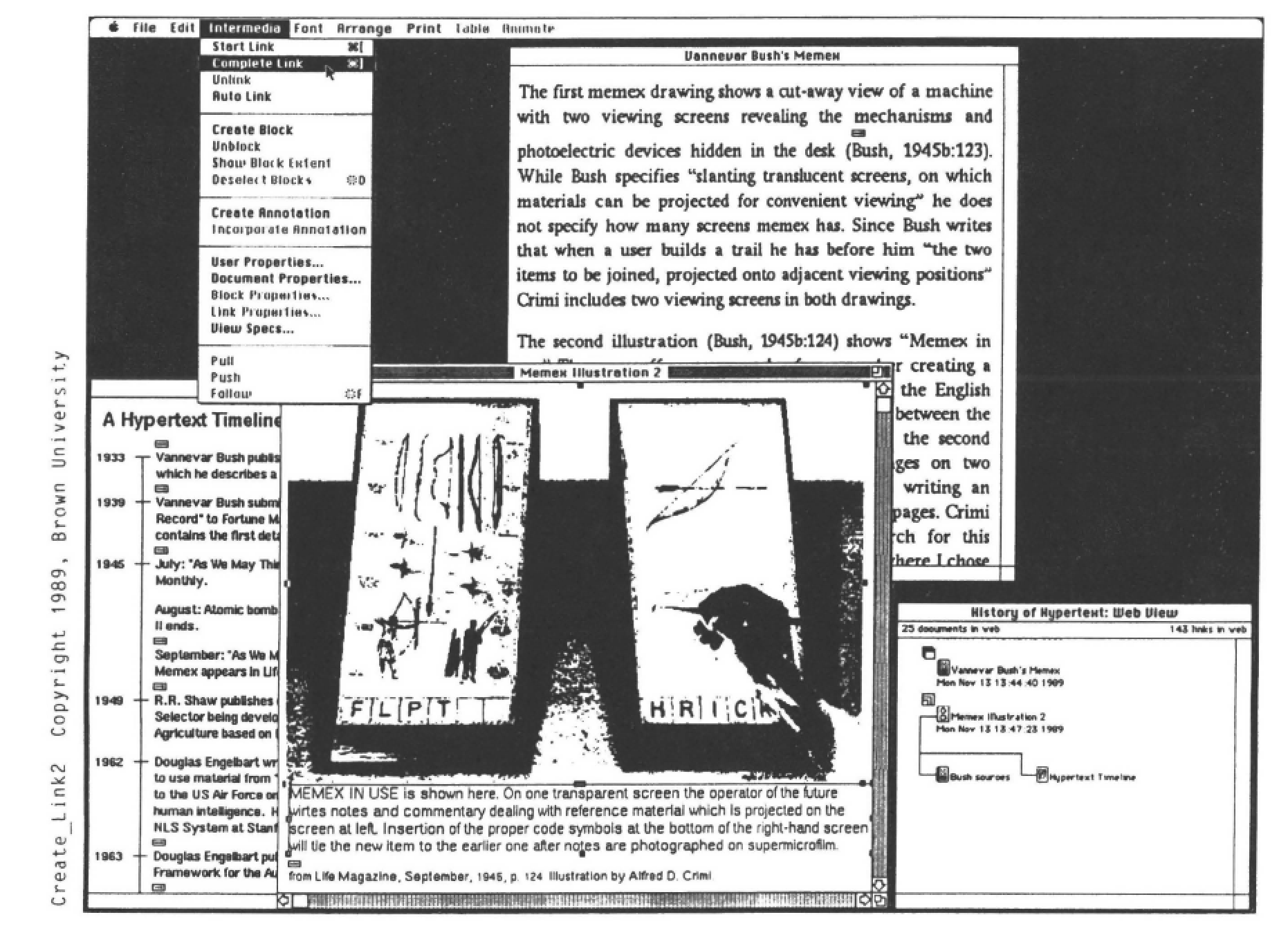

In all candor, the only one of these questions whose answer I'm sure of is the first one: students will obviously be submitting their work to us on diskette(s) or whatever medium replaces the diskette, perhaps with accompanying documenta?tion to explain how to get into the essay. Rejoinders to the other questions are considerably more difficult to find. (See Figures 6.1a and b.)

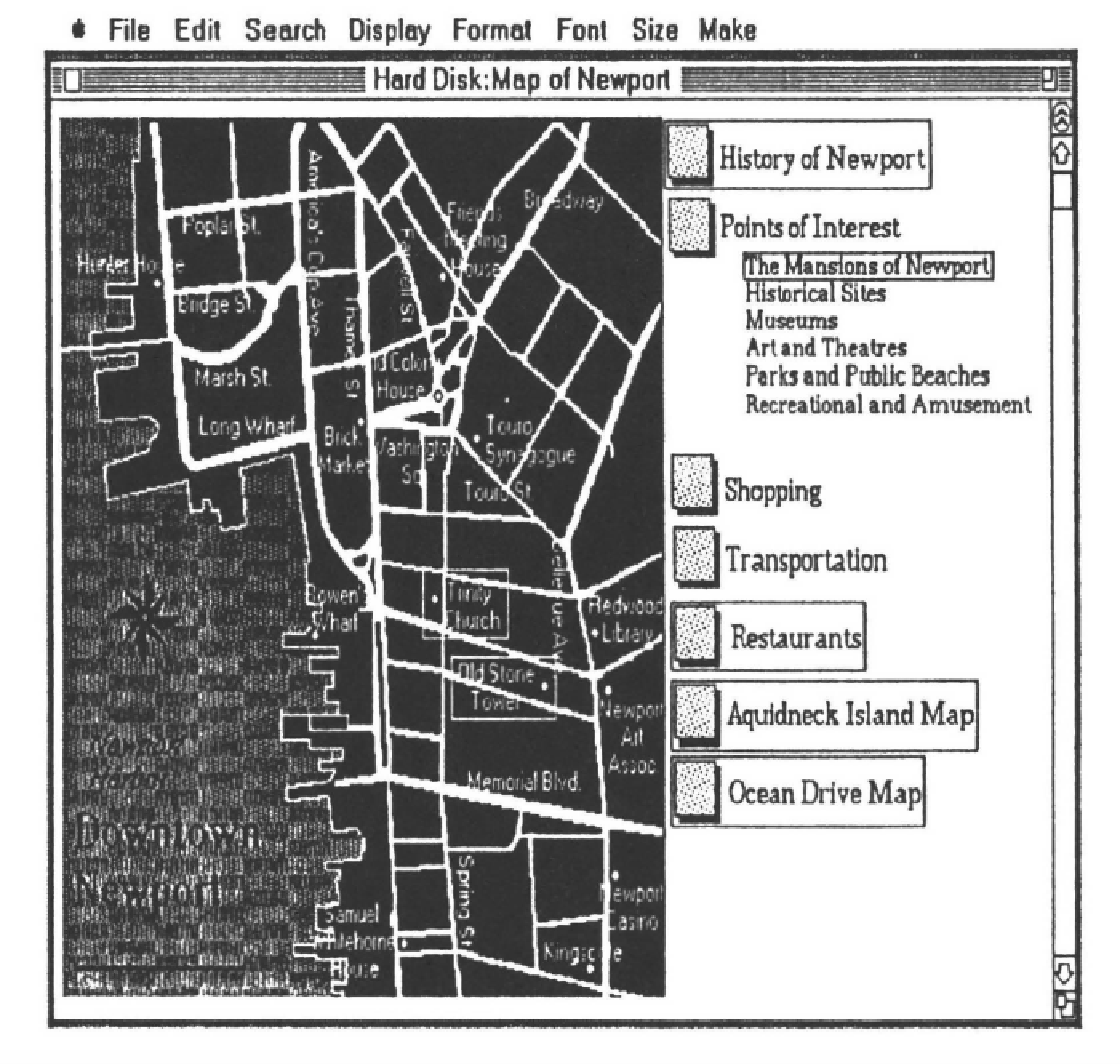

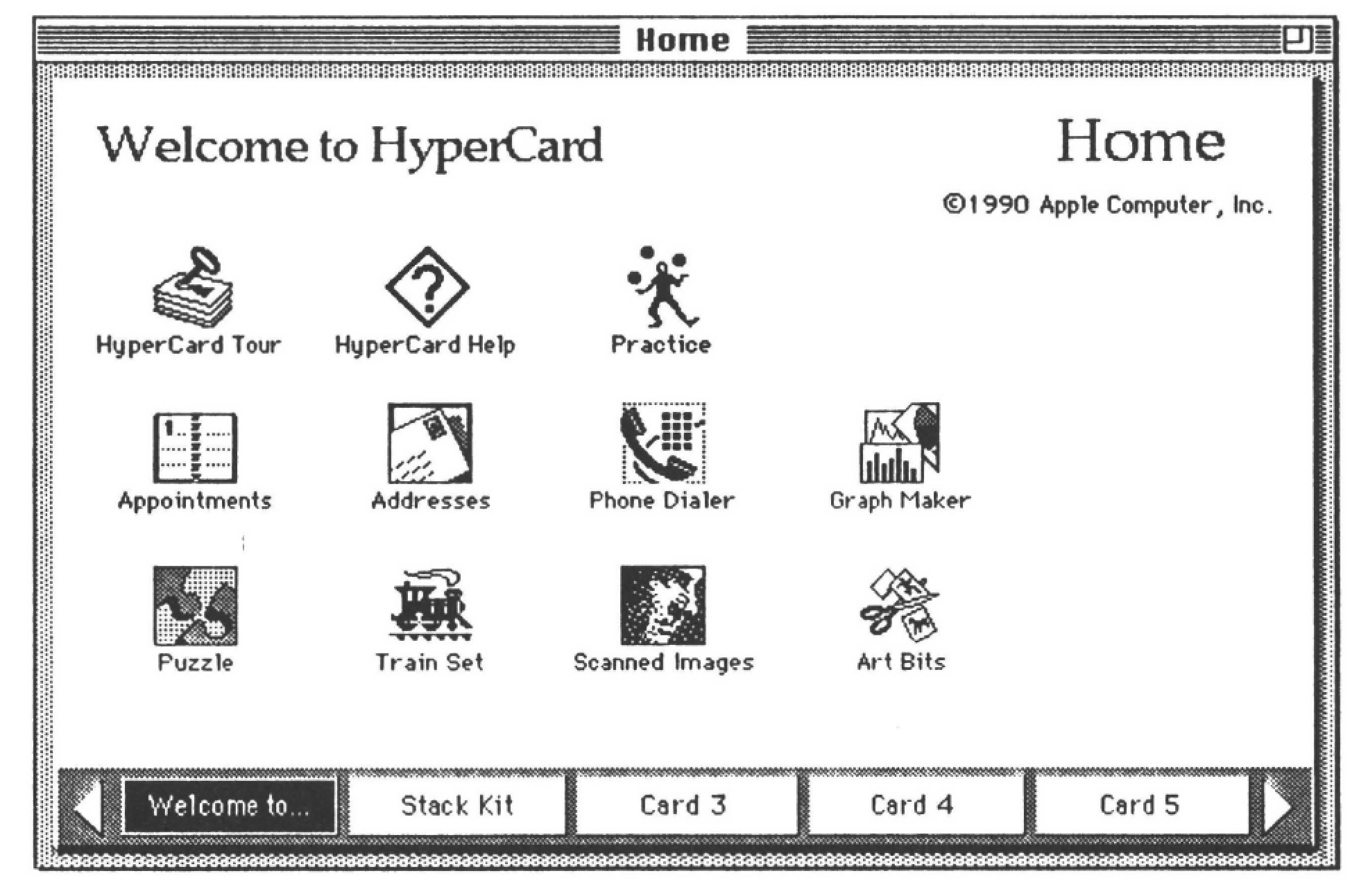

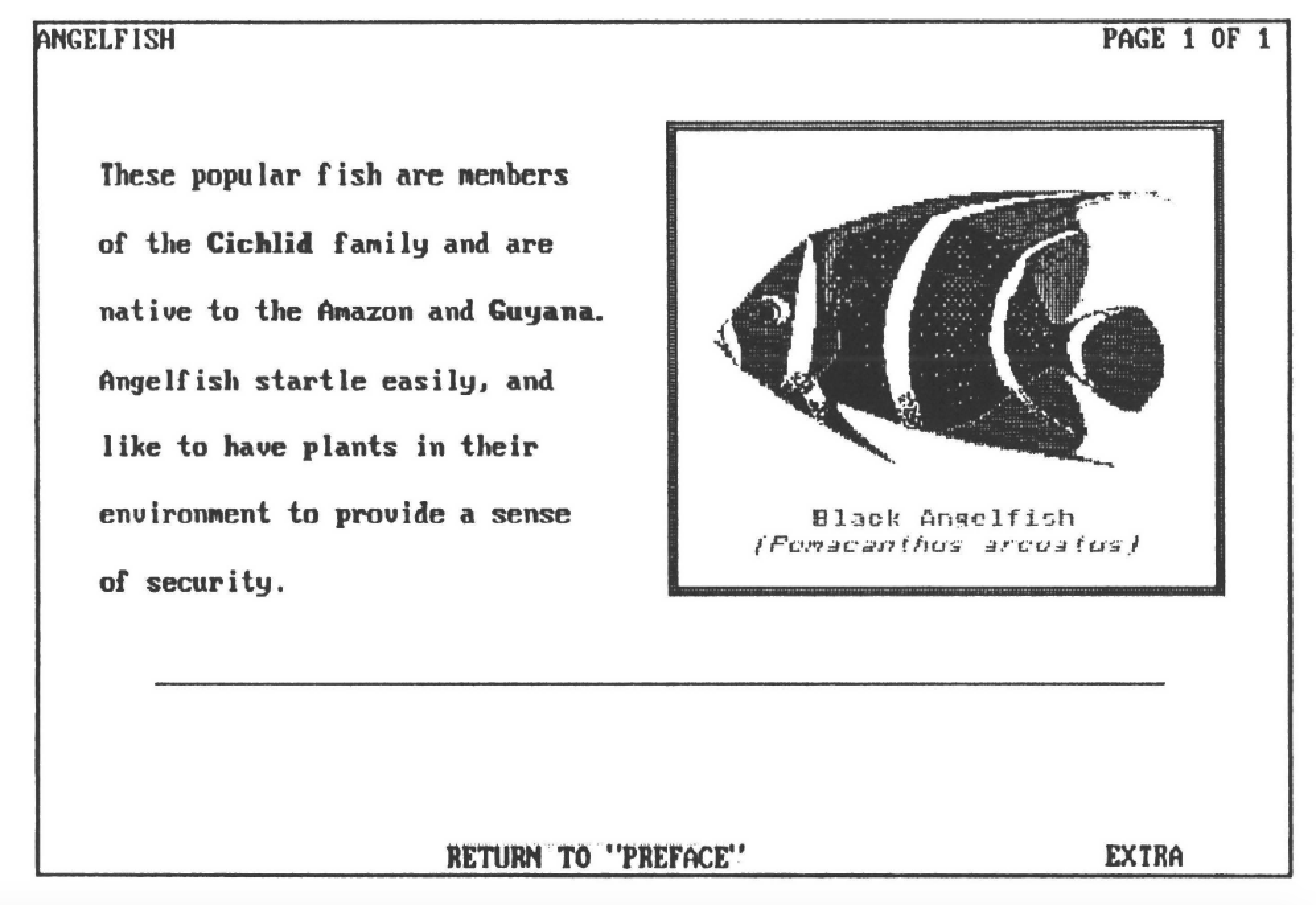

The form of a hypertext depends in large part, on the program used to produce it. Something done in OWL International's GUIDE looks quite different from something done in Apple Computer's HyperCard, which in tum looks quite different from something done in Hyperties or TextPro in the DOS environment, and so forth. Here again we see the difference between word processing and hypertext; there would be something seriously the matter if I had to say that the form of a student essay would depend very heavily upon the particular word processing program she had used. Part of the interest, for me, will be precisely in seeing how each student or group of students will solve-or at least address-the problem of what a hyper-essay should look like now. (See Figures 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4.)

What we're most likely to see at first is what one of my former graduate students, Belinda Gonzalez, referred to as "very extensive footnoting" – or, as another student, Pete Smith, put it, an alluring introductory paragraph of some sort linked

to a variety of explanatory and supporting materials such as online encyclopedias, databases, and so forth. But there is a point at which the extension becomes hyperextended, if you'll pardon the bad pun, so that what you're creating is no longer merely a web of annotations, but actually a system containing multiple frames of reference, multiple windows onto a particular terrain-windows which, as in James's famous House of Fiction metaphor, are created by the pressure of a particular consciousness and which represent the vision of that consciousness. Each window, that is, provides a particular way of seeing – and each way of seeing constructs a new map of the terrain, even a new landscape [James, 1934].

This suggests yet another way in which the technology of composition changes the nature of composition. Hypertext is a wonderful medium for group work [Trigg, et al. 1986]. Thus the hypertext essay might well be the work of multiple authors. One could, for instance, give a whole class a project to work on, with each student responsible for some particular aspect of it. They would work on their projects all semester long, creating individual nodes of their own and defining links among those nodes and other on-line materials available to them. They would have to work out ways of combining and linking all these materials, and creating windows opening out onto different views of the materials they had developed. Ultimately, the class would have to work out (with, of course, the

instructor's active collaboration) how best to link everything, how to define the relationships among the various elements. (See Figure 6.5.)

Personally, I can't wait to try it. Others will be more reluctant, however; for them it will seem to be giving up far too much, and getting far too little in return. And it may well seem too much to ask of our students. 1hls case is eloquently stated by Tina Buck, another of my graduate students, and an experienced teacher. She writes: "I might (and will!) argue that hypertext is radical and perhaps inapplicable to typical freshmen and sophomores because in the first few years of college, students must be taught to think critically, structuredly, etc. I agree that hypertext approaches the way we actually think; but there is much to be said for

the imposition of 'a trained, disciplined mind,' to facilitate communication and thought. I don't know if our typical students are ready for a stream of consciousness approach to their education. In fact, I might argue that you have to under? stand the five-paragraph essay first, before you launch into hypertext. Hypertext is like atonal music: until students understand (traditionally) structured music, they won't like or understand John Cage or Stockhausen."

As I said to Ms. Buck, my own first experience of hypertext was something like my first experience of jazz, when I was about twelve. I had heard about jazz as an improvisational form, I had read descriptions of wild solos, I had heard people like my grandfather saying that it wasn't music. But when I listened to jazz for the first time, I was both disappointed and delighted to find that it sounded like music to my ears! So, too, I when I actually sat down with a hypertext package after reading and thinking about it for a few months, I was most immediately impressed by its resemblance to the kinds of writing I had always known – except that the program I was using lacked the sophisticated word processing features I had come to expect.

Gradually, however, the differences between hypertext and conventional text began to appear. It is certainly true that hypertext disrupts conventional structures and expectations in some very fundamental ways. For instance, where the conventional essay has a single point of departure, an opening paragraph, the hyperdocument offers multiple entry points: the reader chooses where to enter the system. In the same way, the hyperdocument offers not a single conclusion, but rather a number of possible exit-points, and again it is for the reader to choose when and where to leave the system. Most radically of all, the hyperdocument provides many different pathways through the material constituting the system-and again the reader chooses which paths to follow and which to leave for another day. As Ms. Buck indicates, one of the claims most often made for hypertext is that it more closely simulates the interconnectedness of concepts in the mind than conventional text can do [Jones, 1990]. The problem for readers will be in finding a way through and among all the interconnections -and indeed, this may be an insurmountable problem in certain cases, cases where the student author has followed what Ms. Buck described as "a stream of consciousness approach." In any case, it suggests that the traditional opening paragraph may well have to be replaced by a kind of map describing the lay of the land-a map which would have to be accessible from any position in the system.

My first inclination is to agree with the contention that students need to understand conventional structure before understanding hypertextual redefinitions of structure. Sequential text is extremely powerful, and for exactly those reasons that led Nelson and other theorists to critique it: it does indeed impose an arbitrary sequence, an arbitrary structure, upon the material, and requires the reader to submit to that structure. (I do not use the word arbitrary in an evaluative sense, as meaning "pointless": I use it as meaning "lacking intrinsic relation to the matter at hand".) Arbitrary structures (such as the rules of football or chess, the formulae of mathematics, the metrical patterns of poetry, and so forth) are immensely powerful, and never more so than when they have been sanctioned by tradition and we have become forcibly aware – through some change in circumstance, such as the advent of a new medium – of their arbitrariness. To some extent, we commit ourselves to those structures precisely because they are arbitrary: we have to clap our hands to show that we believe. And in committing ourselves to them, we gain access to their beauty and power, and to the beauty and power of the traditions to which they belong.

Having said all that, I want to resist my own inclination to side with those who argue that students should understand traditional ways of doing things first, before we subject them to radical new methods. I want to resist for several reasons, not least of which is that one argument for hypertext is that it more closely approximates the structure of thought in our minds, or the pattern of thought in our minds, than does conventional text. As Douglas Hofstadter has said: "Nothing is a concept except by virtue of the way it is connected up (in the mind, in the memory) with other things that are also concepts" [Hofstadter, 1985].

This is as clear a statement of the conceptual basis for hypertext as one could ask for, though Hofstadter is talking even more generally here about the workings of the mind. It is precisely because hypertext has such a conceptual basis that it can be used to encourage the kinds of rigorous, highly systematic, profoundly critical thinking and writing which many practitioners see as the aim of writing courses. It would work by encouraging exploration of relationships among various objects of study, and by encouraging students to view those objects from a number of different perspectives and to place them within different frames of reference. By creating their own links among various elements in the hypertextual knowledge base, and then explaining and defending the linkages, they could try out different views of their own, and see which ones were most comprehensive and most compelling.

Far from exhibiting mere unedited, self-indulgent stream-of-consciousness, as some may fear, hypertext may and can reveal the most fundamental aspects of intelligence. If concepts themselves are created, are constituted as concepts in being placed into relation with other mental objects, then, if I understand Hofstadter correctly, analogy is the mechanism by which relationships are established, and thus the basis of conceptualization itself. See, for instance, the related essays "On the Seeming Paradox of Mechanizing Creativity" and the long, brilliant "Analogies and Roles in Human and Machine Thinking" [Hofstadter, 1985]. Hypertext links simulate and represent analogies in the mind; linkage is the electronic counterpart to analogy. Thus, hypertext permits student writers (and others, of course) to engage in the formation of concepts, and to explore the basis of their thought.

Conclusion

So I don't see hypertext as being incompatible with previous modes of thought, rather, as the prefix "hyper" indicates, I see it as an extension of text, and of the modes of thought supported by traditional text. It is also an extremely powerful analytical tool; hypertext literalizes much of the current theoretical and practical interest, among teachers of both writing and literature, in the arbitrariness of narrative, discursive, and ideological structures. And that, I think, is both the promise and the threat of hypertext.

In revealing the arbitrariness of our intellectual structures, hypertext may also provide a means of exploring the arbitrary distinctions we make on the basis of race and class and gender, and offer a way to include within the larger totality the voices and visions of those whom we ordinarily exclude, whether knowingly or not. It has been suggested (again by one of my graduate students) that hypertext, like so many other things connected with computers, is really for the elite, the wealthy and privileged. Certainly, the affluent have more access to computers than do the poor or otherwise disadvantaged; it is up to us, I think, to determine whether or not that remains true.

But it isn't true that hypertext is only for the ultra-sophisticated, or only for those in the more rarefied reaches of the academy. Michael Joyce's article "Siren? Shapes: Exploratory and Constructive Hypertexts" [Joyce, 1988] reports eloquently on Joyce's experiments with hypertext as a medium for composition by basic writers in a community college setting. And I have corresponded with a woman in Washington, DC about her plans to use hypermedia in a project to educate economically disadvantaged youth in the worst ghettoes of Northeast Washington.

And finally, perhaps hypertext serves to remind us of the arbitrariness of our commitment to the codex book, forcing us to acknowledge that, in Richard Lanham's words, in recent years "our whole posture has been defensive, based on the book and the curricular and professional structures which issue from it'' [Lanham, 1989, 287]. There was a moment in Western history when writing itself appeared as a revolutionary technology, radically altering the balance of culture and power. Writing succeeded, as Eric Havelock and others have shown [Havelock, 1982], by making itself transparent-by becoming so easy to use, so automatic, that we did not think of it as technology until the computer came along and forced us to reconceive it from top to bottom.

About the Author

John Slatin

John Slatin is an Associate Professor of English at The University of Texas at Austin, and Director of the English Department's Computer Research Lab.

He is the author of several essays on hypertext, and The Savage's Romance (1986), a study of the poet Marianne Moore. He is currently at work on a book about the impact of information technology on research and teaching in the humanities.

References

Havelock, E. A. (1982). The Literate Revolution in Greece and Its Cultural Consequences, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Hofstadter, D. R. (1985). Metamagical Themas: Questing After The Essence Of Mind And Pattern, Bantam Books, New York, NY.

James, H. (1934). (Preface to) Protrait of a Lady, Charles Scribners and Sons, New York, NY 46.

Jones, R A. (1990). To Criss-Cross In Every Direction: or, Why Hypertext Works, Academic Computing 4: 20-21, 30.

Joyce, M. (1988). Siren-Shapes: Exploratory and Constructive Hypertexts, Academic Computing 2:10-14,37-42.

Lanham, R A. (1989). The Electronic Word: Literary Study and The Digital Revolution, New Literary History 20: 265-90.

Nelson, T. H. (1987). Literary Machines, Theodor Holm Nelson, San Antonio, TX.

Slatin, J. M. (1988). "Hypertext and The Teaching of Writing," Barrett, E. (Ed.) Text, Context. and Hypertext: Writing With and For The Computer, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 111-129.

Slatin, J. M. (1990, in press). Reading Hypertext: Order and Coherence in a New Medium, College English.

Trigg, R, SacIunan, Lucy, A., Halasz, F. (1986). "Supporting Collaboration in NoteCards," Conference in Computer-Supported Cooperative Work, Austin, TX, Dec. 3-5.